I left the Russian Orthodox priesthood ten years ago but it wasn’t soon enough. What is your red line?

The evening before my ordination to the priesthood was full of anticipation and anxiety, the feeling one attributes to butterflies in your stomach before a first kiss. Yet, even more, similar to the eve of a wedding. Those same feelings of cold feet began to itch at my toes, and I felt like I wanted to run like the wind or maybe Julia Roberts. The somberness of the vocation I was about to undertake weighed heavily on my mind and soul. This was probably the greatest source of my doubt because I am not a somber person. I am rough around the edges, marred by trauma, and with a tongue that moves faster than my mind.

Am I someone Jesus would call to this ministry? Am I worthy of this?

That morning my eyes welled with tears as the bishop placed the oil on my hands, anointing them for the sacredness of the Eucharist. The blessing of a priest’s body during the ordination service is not that dissimilar from the ritual of last rites. From a theological perspective, this makes perfect sense. The action of becoming a priest is, in function and purpose, the laying down of one's life, joining our sacrifice of certain earthly pleasures with the ultimate death to self found in Jesus. As I repeated the series of vows, I meant them with every fiber of my being. No part of me doubted my commitment to the cause or the cross I would carry. Finally, I stood arm to arm with the bishop and celebrated the Divine Liturgy (the mass) for the very first time.

For nearly eight years, I stood behind the altar and lifted up the bread and wine. I heard confessions, celebrated weddings, and presided over countless funerals. In the course of a day, I could see every part of the human experience. I could begin my morning baptizing a child, the afternoon watching as a couple made a lifelong commitment to one another, and then later that evening standing at the death bed of another couple as one of them finally reached “until death do us part.”

I loved my simple life as a small-town parish priest.

The beauty and majesty of the liturgical church were mesmerizing to me. As the son of a Southern Baptist minister and a Pentecostal mother, this was my great rebellion. I had abandoned the one true faith of Luther’s Reformation for the Whore of Babylon, trading in contemporary Christian music for chants, smoke machines for incense, and track lighting for beeswax candles. The ancientness of the Orthodox faith helped me feel connected to Jesus in a way nothing else had. These songs and smells felt like stepping through the wardrobe into Narnia, placing me into another world entirely where the blind could see and the deaf could hear, and the dead would rise again in glory.

For most of my time in ministry, I felt like an outsider, an outlier of the Church, who just didn’t quite fully belong. I was constantly in trouble for letting colorful language fly during my sermons or making too many pop-culture references. I was a cussing, smoking, drinking priest in motorcycle boots hanging out a punk shows in seedy dive bars.

When the Bible-thumping street preachers would come out and protest our local gay bar, I would stand outside in protest of their bigotry while holding signs from the humorous “I’m With Stupid” to the more direct and gentle “You Are Loved” or “Free Hugs.” Many other clergy were afraid that I was getting too close to “the world” and that I would compromise myself by associating with such people. I continued to protest the protestors in front of the gay clubs and abortion clinics, placing myself at odds with many of my brother priests.

The problem is that I was straddling the fence so hard that I had splinters in my sack.

I was trying to counter the hateful way that folks were saying things and not the root ideologies that were motivating that hate. I didn’t agree with how my fellow Christians responded to those entering the abortion clinic. So instead of holding signs with hateful messages mine said things like, “I will adopt your child.” However, the core of my motivation was not dissimilar to the actions of those I was attempting to counter. At the end of the day, I still believed that abortion was wrong and that people living an “alternative lifestyle” should live an abstinent life. I disagreed with the vitriolic way in which the message was being shared much more than I cared about the theology backing it up.

Worst of all, because I was being kind instead of cruel, I piously believed that my actions were better than that of my siblings in faith. What I failed to see is that it didn’t matter if you invalidated someone with kindness or cruelty, it was the action of not seeing them, hearing them, and accepting them that caused the real pain, not just the way in which the words were said. In many respects, my way was a more horrendous action. I preached love but not acceptance; I preached tolerance but not inclusion. Then, unsuspecting people would come to my parish believing that I did love them just as they were but I fell short.

What I was unable to explain at that time, because I wasn’t being honest with even myself, is that the battle of religious ideology was really being fought in my own heart. I could not reconcile the faith I had been taught from birth and the feelings I had about my own identity. I was a married priest of the Russian Orthodox Church, and yet I knew, deep down, that I was queer and polyamorous. I was fighting my own demons by treating others with the kindness I wished to receive while still condemning the very same feelings.

I claimed to be fighting hypocrisy in the Church, but the truth was that I was also a hypocrite.

(Tashina and I at a Western Rite liturgy)

No, I was not slinging slurs of condemning people to hell or standing on the street corners with verses taken out of context splattered across them… but I was a liar. I was lying about my own identity, about my own feelings, and my own doubts. I would stand behind the pulpit and preach things as truth that I was uncertain of, that I questioned, and yet espouse them as absolutes. In reality, I was far worse than the others that I condemned because I took a “kiss with a fist is better than none” approach. I spoke with love, kindness, and compassion, but the end conclusion was the same; we were all children in the hands of an angry God.

There was a crack in my armor; I just didn’t know it yet.

The year leading up to me leaving the priesthood was a time where I was experiencing some of the most profound doubt, all while appearing to many as more fundamentalist than I ever had. If you were looking toward me from the outside, no part of me appeared to be questioning my faith. I was a stalwart defender of it. I had lost friends over my sudden extremism and Biblical literalism. To those who loved me, it seemed I had become a sold-out Russophile but inside, I was grasping for any straws I could to prevent myself from falling over the ledge into apostasy.

I remained silent as the church condemned Pussy Riot and as pictures began to surface of the violence being enacted on the LGBTQ+ community in Russia.

One of my least favorite phrases is, “There's no point in arguing with people; they never change their mind anyway,” and its close cousin, “protesting doesn’t really change anything.” I’ve heard these words countless times over my life. I’ve come to believe that folks say it to justify away having to do the work, but I'm here to tell you that these sentiments are untrue.

On February 21st, 2012, a group of women entered the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow. They were wearing bright balaclavas to cover their faces, and they began playing a song known as The Punk Prayer, exposing the relationship between Putin and the Russian Orthodox Church.

They were arrested.

It is hard to imagine a time when this wasn’t international news, but it wasn’t. Most people were unaware of the protest and subsequent arrests. But as a priest in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, it became news instantly in my circle.

I received a memo from my immediate superior that we should condemn the protest from the pulpit. Initially, I argued. It seemed odd to me to speak out against people protesting. It did not make sense to my western sensibilities. The right of people to peacefully assemble was so engrained into my consciousness that the outrage didn’t make sense. My superior countered back about how the protest took place on private property and that I wasn’t thinking logically.

I complied with the demand to speak out. I was, after all, a servant of the Church, and it was my duty to submit to those in authority over me, which is exactly what I did.

It is easy for people to forget who I was in light of who I have become. But it can not be stressed enough that I was ultimately compliant with the demands of the Church. I said the things I was told to say. However, I soon could not stop paying attention to this court case that was slowly becoming an international conversation.

Three members of the art collective Pussy Riot were arrested: Nadya Tolokonnikova, Maria "Masha" Alyokhina, and Yekaterina Samutsevich. Each week new information would come out about not only their treatment but the atrocities they wished to expose.

I continued to serve as a priest.

It can not be stressed enough that my silence was complicity and that silence + death.

The war continued to rage within my soul.

Then tragedy struck in the way that it only knows how; in threes. Within the course of a few months, I lost two of my closest friends, one to suicide and another was murdered. I presided over both of their funerals. Neither of them were practicing Christians. Now, according to the faith structure I was adhering to, their souls were in mortal danger. Then, our parish was hit by a flood, and the parsonage where my family lived was destroyed. I was tired, full of doubt, and afraid. Every inch of the town I had called home was now filled with sadness and memories I wished to forget. I could feel my faith slipping away from me and I was scared.

I requested a transfer to a new parish, and the bishop approved it. I took a position as an associate priest at a small church in South Carolina. Little did I know, that this would be my final undoing.

One day my wife and I took a tour of a plantation museum run by a Black lead non-profit designed to expose the reality of the cruelty of slavery in the Antebellum South. As we took the tour of the cabins where human beings were enslaved by their white Christian oppressors, I stepped into one of the buildings that doubled as a church for those who were enslaved on the plantation. On the wall was a written sermon that had been preached there using the Bible to condone slavery. Riddled throughout the sermon were verses that supported slavery. Yet, in 2013 you’d be hard-pressed to find many congregations that would say they supported it now. Instead, as history has been whitewashed, Christianity has now attempted to pretend as if it was some beacon of light that fought against this injustice, when in reality, it had been one of the tools that helped support the slave trade and justified this violence with the scriptures.

I stood there staring at this sermon and was stuck with a sobering thought, “One day, it could be one of my own sermons on a wall like this.” Would it be the homily I preached condemning Pussy Riot? Would it be a transcript of a conversion I once had with a young deacon who confided in me that he was gay, and I told him that he should remain celibate if he wished to be a priest? Was I any different than these pastors who used the scriptures as a weapon to justify hatred and cruelty toward someone else?

On June 26th, 2013 the Supreme Court repealed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) and paved the way for marriage equality to become the law of the land. Instantly, chatter began amongst the clergy of the Russian Orthodox Church, calling for violence towards the queer community. Some suggested that LGBTQ+ people should kill themselves while others prayed for a “Russification of America” so that it would become more aligned with the extremist views of Russian. I watched in horror, knowing that my continued silence would support these words.

I had finally reached my red line.

That afternoon I typed up a brief letter of resignation and posted it online. As I read this letter a decade later, it fails in so many capacities. Yet. I’m sharing it with you because it shows growth. We don’t always have the right words or know the right terms; for example, notice I say polygamy instead of polyamory or I use the term transgendered instead of trans. Even my letter's cadence is so different from how I write now. I didn’t know what I didn’t know, but I was doing the best I could to begin taking the steps to undo all the damage my church had done, and that I had done.

Here is the letter, dated June 26th, 2013:

“For nearly a decade I have served as a pastor, priest and friend to those in need. But my failure today is measured not in what I have done but what I have failed to do. I have remained silent on the issue of marriage equality, and by doing so have failed many people whom I considered to be friends, family, and also those who are suffering throughout the world due to intolerance and bigotry.

I have remained silent out of fear, fear of isolation from my faith, of losing the love and support of my family, and so I have allowed myself to be motivated by that fear. However, the scriptures tell us that 'true love casts out all fear.’

Silently in my heart I have held feelings in opposition to my faith on issues of marriage. I thought that if I remained silent and prayerful then I would eventually come in line with my faith. I have not.

The truth is that marriage ‘between one man, one woman’ is not in the scriptures. There are ever evolving forms of marriage in the scriptures, and seldom was it simply between a singular man and woman.

This fear has held me back, but I can not sit idly by and watch young children kill themselves over the shame of loving someone. It is my religion, or at least the way it is interpreted, that is promoting the shame that is leading to these suicides, to the bullying, and to the assaults.

In my silence I have allowed these actions to take place. When those within the LGBT community have asked me to speak out, I have remained silent, and I am ashamed of myself.

Our hearts are capable of more love than our ancient religions can comprehend, because they are crystalized in a time we have evolved past, and I have allowed myself, and my family, not to progress.

It is for this reason that today I forsake everything that I have known, my religion and my stability, and I choose love. I realize in doing this there will be many who are disappointed in me and angry with me, some will even hate me, but that is a risk I am willing to take because I can no longer live with myself.

To the LGBTQ community, I beg your forgiveness, for my silence and inaction. To my friends who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgendered, questioning, and to the often forgotten, polygamous community, thank you for remaining my friend in spite of it taking me so long to come forward. The time has come for me to join my voice with those who are moving forward.

This leaves me with more questions than answers, I will have to start over completely, begin a new career, and a new life.

Your prayers, positive energy, support, and love is needed now so very deeply.

Nathan Monk”

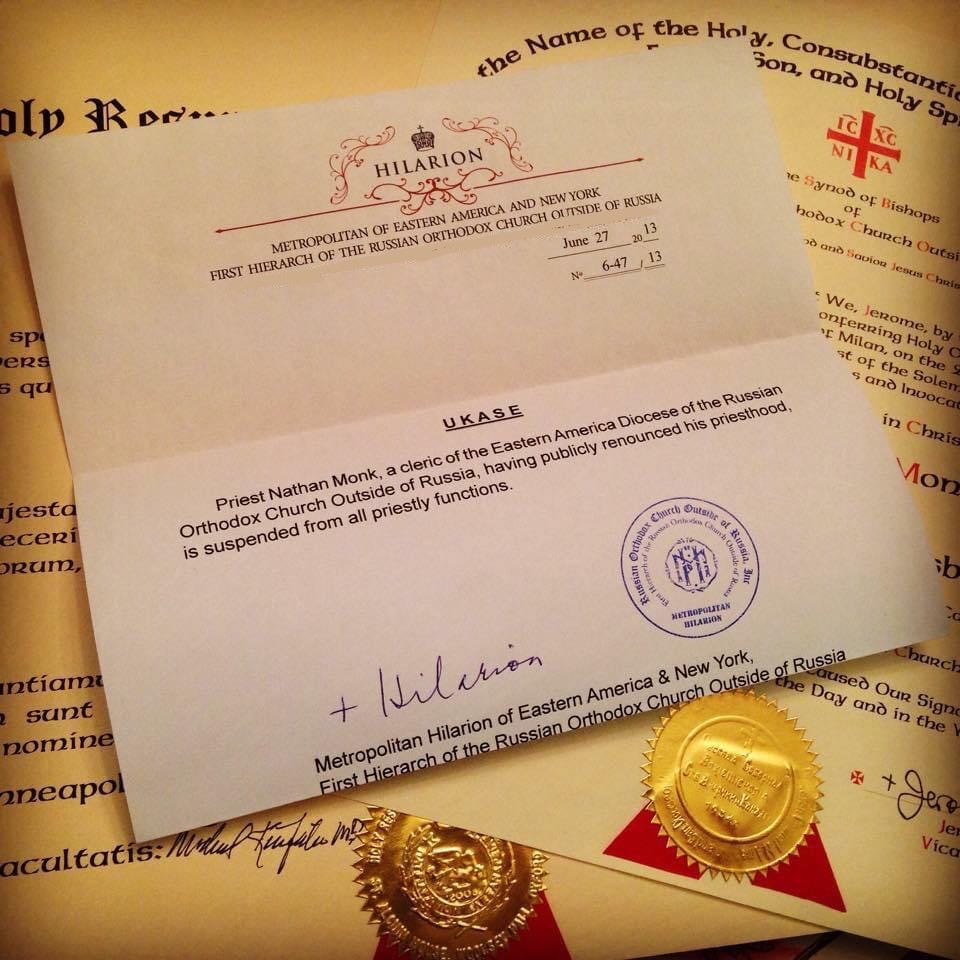

In the aftermath of denouncing the priesthood, I was censured by the church and had my facilities removed. The seminary I attended was closed, the bishop who ordained me disposed, and the ordination of hundreds of priests was placed on hold until the hierarchy could figure out how an apostate like me was allowed into the ranks of the clergy. My family had to flee in the middle of the night from our home, packing only the essentials for fear of retaliation. I received near daily threats of violence against myself and my family. I received a call in the middle of the night telling me to kill myself.

My wife was pregnant with our third child, and we shoved everything we could not our minivan and left our whole life behind.

Every part of my life began to crumble around me. I had lost every friend, every colleague, and I was living in exile. I spent the entire day after I denounced the priesthood calling everyone I knew, apologizing for my silence, for my inaction up to this point. I determined to make the rest of my life an act of contrition.

(A photo of the bishop letter censuring me)

The rockiness and instability turned me into a shell of the person I once was. I became angry, paranoid, and bitter. This version of myself ultimately torpedoed my marriage, and I found myself truly alone with the man I had become. I did not like him very much, and I don’t blame anyone else for not liking him, either.

Then I went to therapy. I got help.

I got better.

It was not easy, it was painful. I had to go deep into my past and face down trauma I had chosen to forget. I had to learn to forgive myself even if others never would. I found a reason to wake up in the morning again. I came out of the closet and started to live life to its fullest.

I have felt a great debt to the members of Pussy Riot for helping me see the light.

Earlier this year, I heard they would be doing a protest and performance in LA in solidarity with Ukraine. I knew I had to go. I needed to be present and to physically join my voice with this cause that helped purchase my freedom from the Church at the expense of their own.

Nadya was so kind and generous to put me on the guest list. When I arrived at the Jeffrey Deitch Gallery in LA, I was brought in before the doors opened to the public. I walked into the main room where projectors were playing a loop of the creation of the art piece Putin’s Ashes. The video showed members of Pussy Riot marching in the desert. I stood alone in this massive gallery, and I wept in that way that only art can bring out.

I cried tears for my silence before I spoke out. Then I cried tears for the terror my family felt as we packed our bags in the middle of the night to escape the threats we received for leaving the church. I cried tears for all of those who had lost their lives in this fight. I cried tears for the thousands more living in fear now as Putin’s War rages on in Ukraine.

When the night was over, I was finally able to thank Nadya in person.

(A photo of me with Nadya and Eva Elfie)

Because protesting changes things, and people change their minds when you argue with them.

Today, as I write this, it has been a decade since I left the church. I have been out of the priesthood longer than I was in it. This is no longer the most significant part of my story; maybe someday it will even become an afterthought. I have been a father longer than I was a priest, my youngest child has never known me as a priest and was not raised in the church. Someday this story of mine will only be a dim shadow of a time that once was.

The word sin, when translated literally, means to miss the mark. It is an archery term for when you are aiming at the bullseye but fall short of it. In this sense, I have sinned against all of my siblings with my time of silence and complicity.

There is a beautiful prayer in the Episcopal Church that is a confession of sins that reads:

Most merciful God,

I confess that I have sinned against you

in thought, word, and deed,

by what I have done,

and by what I have left undone.

I have not loved you with my whole heart;

I have not loved my neighbors as myself.

I are truly sorry and I humbly repent.

For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ,

have mercy on me and forgive me;

that I may delight in your will,

and walk in your ways, to the glory of your Name.

Amen.

For my failures, for my silence in the past, for taking too long to get here, for not loving myself, for not loving you, for now seeing the Divine in each of you, my siblings, I beg your mercy and forgiveness.

Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.

(A photo of me performing my first wedding after leaving the church)

Nathan, thank you for sharing your story. I'm a gay, former Catholic priest. Their are many similarities and differences between our stories, but choosing love is what binds them together. This is a truth that more churchgoers need to hear: "What I failed to see is that it didn’t matter if you invalidated someone with kindness or cruelty, it was the action of not seeing them, hearing them, and accepting them that caused the real pain, not just the way in which the words were said." I've never seen that stated so clearly, so thank you.

Very powerful read. I think if we all sit in our memories for a while, we'll find that we have all been complicit in *something* with our actions. With our inactions. With our silence. Seeking forgiveness from others is important, forgiving ourselves is important as well. Growth like this is painful, and the hardest work many will ever do. But it's the also some of the most important work one can do. Thank you for your willingness to lay out your "sins" for all to see, and for taking a stand.